For a few reasons, some obvious, some not, the history of the southern India is not mainstream in all of India. The history of this region is rich: not just in the events and places,… More

शिवा-बावनी – ५ / Shiva Baavni – 5

The fifth of the 52; (बावनी)। We have an English and a हिन्दी translation. Scroll to the language of your choice.

We are very grateful to Shree Rajendra Chandrakant Rai, our Mentor & Advisor for teaching us the wonderful nuances, and helping us discover the beauty of Mahakavi Bhushan’s poetry.

बाजी गजराज सिवराज सैन साजत ही,

दिल्ली दिलगीर दसा दिरघ दुखन की।

तनीयाँ न तिलक सुथनियाँ पगनियाँ न,

घामै घुमरातीं छोड़ि सेजियाँ सुखन की।।

‘भूषन’ भनत पति बाँह बहियाँन तेऊ,

छहियाँ छबीली ताकि रहियाँ रुखन की।

बालियाँ बिथुरि जिमि आलियाँ निलन पर,

लालियाँ मलिन मुगलानियाँ मुखन की।।

शब्दार्थ:

बाजी = घोड़ा । गजराज = बड़े-बड़े हाथी । दिलगीर = (फ़ारसी) दुखी, रंजिदा । तनीयाँ = चोली । तिलक = (तिरलीक़) एक तरह का ढीला-ढाला कुरता; पगनियाँ = पगों में पहनने की जूतियाँ, पन्हइयाँ । सुथनियाँ = पायजमा । घामैं = घाम में, धूप में । घुमरात = घबरा कर भागती फिरती हैं । रूख = पेड़ । आलियाँ (अलियाँ) = भौंरा । नलिन = कमल । लालियाँ = सुर्खी, सुन्दारता ।

भावार्थ:

शिवाजी महाराज की सेना के द्वारा अपने घोड़ों और हाथियों को युद्ध के लिये सजाते ही दिल्ली के बादशाह की दशा बिगड़ने लगती है। इसको देखकर, उनकी स्त्रियों के सिर पर वस्त्र, पाजामा, और जूतियाँ भी व्यवस्थित नहीं रह पाति। सेज पर सोने का सुख त्याग कर धूप में इधर-उधर भागती फिरती हैं।

भूषण कवि कहते हैं कि, जिन नई-नवेली दुल्हनों को अपने-अपने पतियों की बाहों में विश्राम करने का सुख उठाना चाहिये था, वे महल के बाहर जंगलों में पेड़ों की छाया तलाश करती भटक रही हैं। उन सुंदरियों के केश इस तरह बिखर गये हैं, जैसे कमल पुष्प पर भंवरों के झुंड उड़ रहे हों। मुगल-स्त्रियों के मुखों की लालिमा मलिन पड़ गयी है।

काव्य सुशमा:

- उपमा अलंकार

- अनुप्रास अलंकार

- भय का मनोवैज्ञानिक प्रीभाव कैसा होता है, इसका चित्रण कुशलतापूर्वक किया गया है

- अतिशयोक्ति अलंकार

English Translation

baajee gajaraaj sivaraaj sain saajat hee,

dillee dilageer dasa diragh dukhan kee.

taneeyaan na tilak suthaniyaan paganiyaan na,

ghaamai ghumaraateen chhodi sejiyaan sukhan kee..

‘bhooshan’ bhanat pati baanh bahiyaann teoo,

chhahiyaan chhabeelee taaki rahiyaan rukhan kee.

baaliyaan bithuri jimi aaliyaan nilan par,

laaliyaan malin mugalaaniyaan mukhan kee..

Word-Meanings:

बाजी = horse; गजराज = elephant; दिलगीर = (Persian word) sad, depressed; तनीयाँ = blouse, bodice; तिलक = a loose kurta; पगनियाँ = shoes; सुथनियाँ = churidaar or pajamas; घामैं = in the sun; घुमरात = wandering in fear; रूख = tree; आलियाँ (अलियाँ) = bees; नलिन = lotus; लालियाँ = beauty.

Essence:

As Shivaji’s army, with its horses and elephants gets ready, the state of the kings of Delhi is that of sadness, depression and fear. Their clothes, accessories, and footwear are unkempt and bedraggled. The women of the palace have left the comfort of their rooms and run helter-skelter in the sun.

The newly weds, who should have been in the arms of their beloved are running in the forests, seeking shelter and shade with the trees. Their hair is dishevelled and resembles a swarm of bees over a lotus; their faces have paled and accentuated their pallor.

संदर्भ / References

- पं॰ हरिशंकर शर्मा कविरत्न। शिवा-बावनी, टीका-टिप्पनी, अलंकार तथा प्रस्तावना सहित। आगरा: रामप्रसाद एण्ड ब्रदर्स

- आनन्द मिश्र ‘अभय’।। शिवा-बावनी, छत्रसाल दशक सहित। लकनऊ: लोकहित प्रकाशन। २०१२

- आचार्य विश्वनाथप्रसाद मिश्र। भूषण ग्रंथावली। नयी दिल्ली: वाणी प्रकाशन। २०१२।

Humayun’s Exile and Return

The Background

Babur descended from the Hindukush mountains into the plains of Punjab and created an empire spanning from Badakhshan to Bihar.

He had many sons out of whom only four were important – Humayun (the eldest), Kamran, Askari and Hindal (the youngest).

Babur died in 1530 leaving a fragile legacy in the more fragile hands of his 20-year old son Humayun, challenged by the nobles and Kamran. Every opponent was waiting for the right opportunity to hit. Humayun, however, relied on astrology and stars instead of SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats).

Indian Enemies and Clashes

Humayun had to face two threats – Sher Shah Suri of Bihar and Bahadur Shah of Gujarat, who had also captured Malwa and Mewar. Humayun failed to capitalise on his initial upper hand over both the rivals. Although Bahadur Shah was killed by the Portuguese in 1537, Sher Shah Suri took Bengal in 1538 and emerged as the biggest single threat to him.

The Run and Chase Game in India

Humayun fled Delhi to Lahore along with his family, few loyal courtiers, and bodyguards. At this time, his brother Kamran was hostile as ever and Askari was with Kamran at Kabul. Hindal was 21, and had proved his administrative capabilities in the past decade. So his ambitions couldn’t be discounted either. Apparently Humayun was not welcome at Kabul. Instead, Kamran tried to join hands with Sher Shah.

Sher Shah was quick in capturing the Punjab. Sensing the danger of possible nexus between the pursuing Afghan and his brothers, Humayun was left with no choice except fleeing south across the Thar desert to Sindh, then ruled by the Arghun sultan Hussain Shah. Fortunately for Humayun, Hindal pledged allegiance to him.

Humayun reached Sindh in 1541 and unsuccessfully tried to win over Hussain Shah Arghun, an unexpected favour from a person whose father was expelled from Kandahar in 1522 by Humayun’s father, Babur. Although Hussain Shah allied himself with Babur, he initially refused help to Humayun. Hindal tried to besiege Sehwan, an Arghun stronghold in northern Sindh. All the efforts proved futile.

In the meantime, Humayun married Hamida Banu, the daughter of a Shia Sufi spiritual master from Sindh named Shaikh Ali Akbar Jami, in September, 1541. Interestingly, the chief consort of Humayun, Bega Begum, was married to him roughly at the time when Hamida was born. There are hints of existence of unexpressed mutual feelings between Hamida and Hindal. But Hindal expressed it in a rather strange way after Hamida’s marriage to Humayun, by deserting him. Then the loyalties started deserting him increasingly.

Being refused by Maldeo Rao of Jodhpur (Marwar) for help, Humayun sought help of the Sodha Rajput, Rana Prasad of Amarkot (now Umerkot, Sindh). He, along with the pregnant Hamida Banu, reached Amarkot in August, 1542. Jalal (future Akbar) was born at Amarkot in October, 1542.

In 1543, finally the Arghuns of Sindh allied themselves with Humayun and he proceeded towards Kandahar with his ‘new army’ with a hope to unite with his brothers, then in Kabul, to reconquer ‘Hindustan’.

But he crossed the Indus, to reach near Kandahar in late 1543, to find that Askari was forced to acknowledge the authority of Kamran while the refusal by Hindal had earned him imprisonment. On the other hand, Sher Shah started building the strong and impregnable strategic fort of Rohtas near Jhelum in Pakistan’s Punjab (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site) to check the entry of the Timurids into India. To make matters worse, Askari was ordered by Kamran to capture Humayun who camped near Kandahar.

When Askari approached Humayun, he had nothing left in India to rely upon. He made quick yet calculated decision to flee further westward to the Shia Safavid Persia. He left behind the fourteen-month old Jalal (Akbar) at the mercy of the invaders. Askari not only adopted Jalal but also persuaded Kamran not to be harsh upon the baby. Kamran probably took Jalal as hostage. Nevertheless, the childhood of Jalal was to be spent in adventures in and around Kabul. Until Humayun’s return, Askari took care of Jalal and ensured his safety from Kamran.

Asylum in Persia

Humayun, Bega Begum, Hamida, and their forty loyal bodyguards took the northern route to Herat, then under the Safavid Persia, where they reached after a month-long torturous journey. At least here they received a royal welcome. But, it wasn’t unconditional.

At this time, Tahmasp I was the Safavid Sultan, the second one in his lineage, ruling since 1524. The imperial capital was Isfahan (Esfahan). The meeting between Humayun and Tahmasp in 1544 is depicted through a painting in the Chehel Sotun Palace of the city. Apparently, Hamida’s illustrious Shia background must have had strengthened the bonds between the two monarchs.

Secondly, Humayun was to cede the strategic fort and town of Kandahar to the Safavids as soon as he captured it.

Such conditional asylum was nothing unusual for any prudent ruler like Tahmasp who repeated the brilliant move in the case of the fugitive Ottoman prince, Bayezid, who happened to be very capable military leader and brilliant administrator, and could apparently succeed Suleiman the Magnificent, the greatest Ottoman emperor.

So Tahmasp supported Humayun with 12,000 troops to recover his lost domains, except Kandahar.

Regaining the Lost Ground

Humayun besieged and took Kandahar from Askari in mid-1545. To add to his happiness, a simultaneous siege at Kalinjar in India killed his arch-rival Sher Shah Suri in May. Nevertheless, Delhi would elude him for a decade.

Humayun proceeded to Kabul to confront Kamran, who found himself isolated as most of his allies and loyalists joined Humayun and forced him to leave Kabul without offering any resistance. This is how Humayun got Kabul in November, 1545.

Humayun showed his characteristic lethargy by not hunting down Kamran at this juncture. He instead indulged in festivities as he joined his lost son Jalal (Akbar) after a long. But the evasive Kamran managed to tease Humayun. Kamran took and lost Kabul twice, losing it forever in 1550. His resolution to dethrone Humayun was still there in his vindictive soul.

This was relatively easy time for him. In 1546, Humayun married Mah Chuchak Begum, a lady of military genius from Kabul. But this was to make the Kabul affairs complicated for his son Akbar as she bore Humayun two sons – Hakim and Farrukh.

In an attempt made by Kamran to retake Kabul in 1551, Hindal lost his life between Kabul and Peshawar. As a gesture of sympathy and gratitude, Jalal (Akbar) was married to Hindal’s daughter Ruqaiyyah Begum, who remained the chief consort of Akbar. Askari’s daughter Sakina too was married to Akbar.

Kamran did not give up. He asked for help from Sher Shah’s son, Islam Shah and the Ghakkars of western Punjab (now in Pakistan) who were loyal to Humayun, but was refused by both and instead captured and handed over to Humayun in 1552. A confused Humayun was under tremendous pressure this time from his loyals as the latter had lost too much and suffered from miseries for over a decade due to the former’s ill-sighted actions and indecisive behaviour. Humayun finally blinded Kamran and sent him on Hajj to Mecca, where he died in 1557.

Jalal (Akbar) was made the governor of Ghazni and he showed his mettle which he was going to prove in India over the rest of the 16th century.

Finally Delhi !

Sher Shah died in 1545. He was succeeded by Islam Shah Suri. In November 1554, Islam Shah Suri too died in Delhi, followed by quick successions to the throne. Islam’s minor son and successor, Firoz Shah’s was assassinated by his uncle, Muhammad Adil Shah. Adil Shah was overthrown by his brother-in-law, Ghazi Khan alias Ibrahim Shah. But Sikandar Shah declared his independence at Lahore and defeated Ibrahim at Farah near Mathura and became the emperor. This all happened within just six months, thus breaking the backbone of the Sur Empire.

Humayun had patiently waited for about 15 long years for the right moment to strike. And finally his penance paid off. With no rivals either in vicinity or between him and Delhi, he marched towards the de-facto capital of ‘Hindustan’ since centuries.

When the Sur civil war was going on, Humayun took Rohtas Fort, which Sher Shah had built to check Humayun’s entry into ‘Hindustan’, then Dipalpur and Lahore in early 1555. Finally, the decisive battle took place at Sirhind on 22nd June, 1555 in which, Sikandar Shah Suri was defeated and fled towards the Himalayas in today’s Himachal Pradesh. Still, Muhammad Adil Shah posed a considerable threat along with his trusted general, Hemchandra or Hemu. It was now Adil Shah’s and in effect, Hemu’s turn to wait for the better chance.

Humayun triumphantly entered Delhi in July, 1555. It was a hard won victory which made him realise that reliance upon astrology is good only for entertainment and not for practical and tactical judgements. But this time, ironically, he was proved wrong again, not by any foe but a mishap. He lost his life in late January, 1556 due to the injuries sustained while descending the stairs of Sher Mandal (probably Sher Shah’s library or perhaps an observatory) in Old Fort (Purana Qila) in Delhi.

More than three centuries later, after this Mughal Empire established by Humayun was really over in all respects, the British historian Lane Poole rightly said – “he tumbled out of life as he had tumbled through it.”

Persia vis-à-vis the Mughal Empire

Mughals were already highly Persianised. In fact, the term ‘Mughal’ itself is the Persian word for ‘Mongol’. Humayun’s exile opened the gates for further and faster Persianisation and if one is honest enough, he would call Mughal Empire a ‘Persianate’.

References :

- Humayun-nama by Gulbadan Begum

- The Life and Times of Humayun by Ishwari Prasad

- Humayun Badshah by S.K.Banerji

- Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India by J.L.Mehta

- The Mughal world : Life in India’s Last Golden Age by Eraly Abraham

- Akbar, the Greatest Mogul by S.M.Burkhe

- Medieval India under Mohammedan Rule by Stanley Lane-Poole

- Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World by Ruby Lal

“Civilization is a stream with banks. The stream is sometimes filled with blood from people killing, stealing, shouting and doing the things historians usually record, while on the banks, unnoticed, people build homes, make love, raise children, sing songs, write poetry and even whittle statues. The story of civilization is the story of what happened on the banks. Historians are pessimists because they ignore the banks for the river.”

~Will Durant

Image: Bidar Fort, Bidar, Karnataka

Of Demand, Supply, and Hunger

A few decades should count as a small blip in the long history of human civilization. The last few decades, however, have been immensely transformative for the human race. Many objects and experiences that were a persistent part of human story in the preceding millenniums are fading away quite fast. Mass hunger was one of them. It came often, it came hard and it left some deep hollow spaces in the tree of humanity.

The story of an officer’s efforts in dealing with mass hunger in a small town in Central India in 1833, and eyewitness accounts of other famines offer us an insight into what it was like to live through a calamity like this.

Background

The end of Anglo-Maratha wars in 1818 effectively concluded the British conquest of India, with the British now gaining control of most of India. Among the newly conquered territories a large portion was what is now known as the state of Madhya Pradesh. The ancient land of Gonds, Satavahanas, Guptas, Chandelas, Bundelas, Mughals and Marathas was now ruled by the mega corporation: the East India Company.

The company which was initially chartered to explore the “trade of merchandize” with India was now deeply ensconced not only in the matters of Diwani (Revenue and Civil Administration), but also for Nizamat (Criminal and Police Administration). People in central India who recognised their rulers through clans, now saw officers coming from far away lands as representatives of the faceless corporation. Some of these officers found themselves in a position where their actions had a very significant impact on a large number of people. Many officers were acutely aware of the burden tied to their bureaucratic strings. Among them, there was Sir William Henry Sleeman.

Sleeman soon found himself tackling the wide array of administrative tasks in the course of his postings in the region. Among them were matters of revenue collection, law and order, Sati burnings and other social reforms, treasury and mint, agriculture, thuggie and famines.

The Hunger Spiral

Famine was a frequent occurrence. Droughts, floods, warfare, locusts, monsoon, and many other factors caused frequent famines in medieval India. The Jataka tales, Jain literature, and other ancient texts mention severe famines in India. Contemporary writings during Mughal period mention severe famines of great intensity. During the reign of Shah Jahan some three million people are said to have perished due to famines.

It often started with crop failures, which led to food shortage, and increase in the price of food grain. In those closed loop economies, without much transportation and communication links with the outside world, speculation played a vital role. Nearly every generation had seen serious famines and people relied on old tales to make significant decisions that weighed heavily on their families’ fate. One old saying went:

सावन कृष्ण एकादशी, यदि गरजै अधिराक। तुम पिय जाओ मालवा, हम जावें गुजरात।।

(If there are heavy thunders during the Krishna Ekadashi of Sravan month; oh father, you go to Malwa and I will go to Gujarat)

Malwa was seen as a more fertile land where famines were less frequent. With the spread of panic, started a trail of migrations. Not knowing what to do, poor families abandoned their farms, homes, and cattle and often moved towards the centres of authority – local rulers or the administrative headquarters. Many rulers organised charity kitchens. As the famines intensified, torrents of poor, famished people flowed to cities.

At the sight of scarcity, the agriculture economy froze like a scared animal. The value chain consisted of farmers, traders, transporters, financiers, and consumers. Traders would often hoard the grain, sensing headwinds. Shortage of cattle added to the transportation challenges. The produce was carried on bullocks, covering 6-8 miles a day. Prices doubled for every 100 miles of transportation, and tripled in a season of scarcity. Insolvency of any debtors crippled the money supply in the markets dominated by small, closed communities. With the complete shutdown of a functioning society, the focus eventually came to the one and only essential commodity – FOOD

Those Sights, Sounds and Stench

Contemporary observers of famines describe a society stricken with hunger in chilling detail.

Still fresh in memory’s eye the scene I view,

The shrivelled limbs, sunk eyes, and lifeless hue ;

Still hear the mother’s shrieks and infant’s moans,

Cries of despair and agonizing groans.

In wild confusion dead and dying lie;–

Hark to the jackal’s yell and vulture’s cry,

The dogs’ fell howl, as midst the glare of day,

They riot unmolested on their prey !

Dire scenes of horror, which no pen can trace,

Nor rolling years from memory’s page efface.~ Charles John Shore Baron Teignmouth (referring to the Bengal famine of 1770)

(Memoir of the Life and Correspondence of John, Lord Teignmouth, Volume 1)

Poor people, now homeless, without any possessions, were seen wearily dragging themselves along major roads. Those left behind in their villages, each passing day played Russian roulette with death; weighing the odds of improvement in the situation against the risk of abandoning their home, while they had the means and physical energy to do so. The definition of “food” started changing. Seed-grain was consumed, damaging the prospects of next year’s crops. Shrubs like Jharberi and many plant seeds became a large portion of diet. Grass, tree leaves were consumed. When the famines intensified, many cattle were slaughtered or abandoned by their owners.

The abandoned animals howling in agony of thirst and hunger went eventually silent. The stench of animal carcasses was felt in the air. The surviving animals, in their bare bones, scourged for food in shrubs, roots, and trees in extreme desperation. F.H.S. Merewether describes:

As we were coming back from the court-house, the Commissioner pointed out to me a few frameworks of cattle on the wayside; they were absolutely burrowing in the ground, like pigs, to get at the roots.

And it subsequently moved to humans. Younger children, in absence of prolonged absence of meals, were the most vulnerable and often perished quickly. In desperation, many children were sold into slavery. The practice of selling children during famines was an old one. Ain-e-Akbari mentions that Akbar had legalised the practice during the times of famines and distress, and gave their parents an option of buying them back later.

The malnourished children developed a swollen abdomen due to protein deficiency, a symptom known as Kwashiorkor. This was a fatal stage and very few children survived after that. The children tottered with a feebly, bereft of any childlike demeanour. Merewether describes:

One of the first objects I noticed on entering was a child of five, standing by itself near the middle of the enclosure. It’s arms were not so large round as my thumb its legs were scarcely larger; the pelvic bones were plainly shown; the ribs, back and front, started through the skin, like a wire cage. The eyes were fixed and unobservant; the expression of the little skull-face solemn, dreary and old. Will, impulse, and almost sensation, were destroyed in this tiny skeleton, which might have been a plump and happy baby. It seemed not to hear when addressed. I lifted it between my thumbs and fore-fingers; it did not weigh more than seven or eight pounds. Probably its earliest recollections were of hunger, and it could never have had a full meal. It was now deserted by those who had brought it into the world, or they were dead; its own life would be gone in a day or two. Its skin was quite cold. dry and rough. Pain had been its only experience from the first; it had never known or imagined the comforts that babies have.

As for adults, death came in many forms. Tribals wandered into forests in search of food, disoriented, and died of exhaustion there. Shortage of herbivorous animals caused wild beasts to wander into human territories and many people were killed by tigers. Many families chose to kill themselves with opium or other means after having all provisions exhausted. Pandita Ramabai, a famine survivor describes:

At last the day came when we had finished eating the last grain of rice – and nothing but death by starvation remained for our portion. Oh, the sorrow, the helplessness, and the disgrace of the situation •••• We assembled together and after a long discussion came to the conclusion that it was better to go into the forest and die there than bear the disgrace of poverty among our own people. Eleven days and nights – in which we subsisted on water and leaves and a handful of wild dates – were spent in great bodily and mental pain. At last our dear old .father could hold out no longer the tortures of hunger were too much for his poor, old, weak body. He determined to drown himself in a sacred tank nearby and thus to end all his earthly suffering ••• It was suggested that the rest of us should either drown ourselves or break the family and go our several ways.

Weakened bodies crawled around waiting to die, trying to avoid being mauled by impatient jackals and vultures. Sleeman wrote about the famine in Sagar:

At Sagar, mothers, unable to walk, were seen holding up their infants and imploring the passing stranger to take them in slavery, that they might at least live. Hundreds were seen creeping into gardens, courtyards, and old ruins, concealing themselves under shrubs, grass, mats, or straw, where they might die quietly, without having their bodies torn by birds and beasts before the breath had left them.

The Intervention Dilemma

In 1833 Sleeman was in the middle of his famous Thuggie trials, while serving as a magistrate in Saugor (Sagar) district in Bundelkhand. The autumn rains failed, and the spring crops could not be sown owing to the hardness of the ground, caused by the premature cessation of the rains, followed by the outbreak of famine. As the famine intensified in the countryside, streams of people started migrating towards Sagar, causing the all too familiar explosive situation.

Sagar was a major cantonment centre. Major Gregory, the military officer posted in Sagar, unsure of the future supply of grain and apprehensive of discontentment among his soldiers, decided to procure a large supply of grain at high prices. Everyone, consumers as well as traders, saw this as a certain signal of an impending crisis. Soon the markets got exhausted of any known supply of food, and the trade stopped.

Hoarding compounded the problem. The merchants hid the grain in underground granaries, pits inside their homes and warehouses. The greed for profit caused the merchants to accumulate grain, and the fear of rioting or coercive action by authorities caused them to hide it. This made it hard for authorities to estimate the actual quantity of grain available in the market. Quite often the grain rotted in the traders pit without reaching the markets. This led to authorities raiding the traders storage, confiscating it or forcing them to sell it at a discounted prices. Arthashastra by Kautilya recommended making the rich “vomit (वमनं)” their wealth during harsh famine.

With the intensifying famine, shortage of food and arrival of migrants, Sleeman faced the pressure to act against the traders. The kotwal of Police declared that a crisis was impending and the police and others would be unsafe unless such action is taken.

Sleeman had been a long advocate of free trade. His concern was that the forcing a trader to sell his stock deprived him of his cash flow. In absence of incentives and the fear of such actions discouraged the traders to import grains from elsewhere, which in the ensuing period made things much worse.

But was there any grain from other districts to import? Sleeman got an estimate of stock in Jabalpur and other places, which indicated that there was stock.

He showed his pledge to Major Gregory, assuring that no amount of clamour should ever make the administration violate the pledge given to the traders, and he was prepared to risk his situation and reputation as a public officer upon the result.

This proclamation was issued in the city in the afternoon and further police force was deployed to provide assurance to the traders.

As Sleeman had hoped, the markets started to open. Grain started to appear in the market, and traders, with their apprehensions reduced and cash flows operating again, sent out to import grain from other districts. The high prices attracted more people to venture into the trade, and soon the prices started coming down.

The crisis, at least for a while, was avoided.

Epilogue

A lot of water has passed under those medieval bridges crossed by Sleeman in the 1800s.

He went on to become the Commissioner for the Suppression of Thuggee and Dacoity, and later a resident a Gwalior and eventually at Awadh, with Wajid Ali Shah. After spending 47 years in India, he died in February 1856 near Ceylon (Sri Lanka) at the age of 67, on the way home. He was buried at sea.

Sleeman’s footprints can be traced across the landscape of central India. Among them, a bounty of literature describing the world he saw. Statistical records of his time, a variety of sugarcane he brought from Fiji, first Dinosaur fossils in India found by him, the modifications he made in the Indian penal code, the institutions he establishe and a little village called Sleemanabad near Jabalpur.

The British administration presided over many severe famines, causing several millions of deaths. India gained independence in 1947. The Food Corporations Act of 1964 resulted in the establishment of Food Corporation of India in 1965.

In 2012, Madhya Pradesh became the second largest wheat-producing state in India, much of the wheat comes from the region around Sagar. There has not been a single large-scale famine in India since independence. That stench, those shrieks and groans, howling of animals and that stench of death have been largely forgotten.

Sleeman’s collectorate in Sagar was demolished in 2016 to make way for new construction. Few other relics of that era survive.

Etched in the DNA of humanity, there are traces of events that created major voids in the genealogy trees. Somewhere around them there are also markers of a day in a bygone era when some hungry people were able to eat.

References

- Memoirs on the History, Folk-lore, and Distribution of the Races of the North Western Provinces of India Link

- Rambles and recollections of an Indian official

by Sleeman, Sir, William Henry Link - Indian Famines: Their Historical, Financial, & Other Aspects, Containing Remarks on Their Management, and Some Notes on Preventive and Mitigative Measures Link

- The Starvation Process: Dearth, Famishment and Morbility. Link

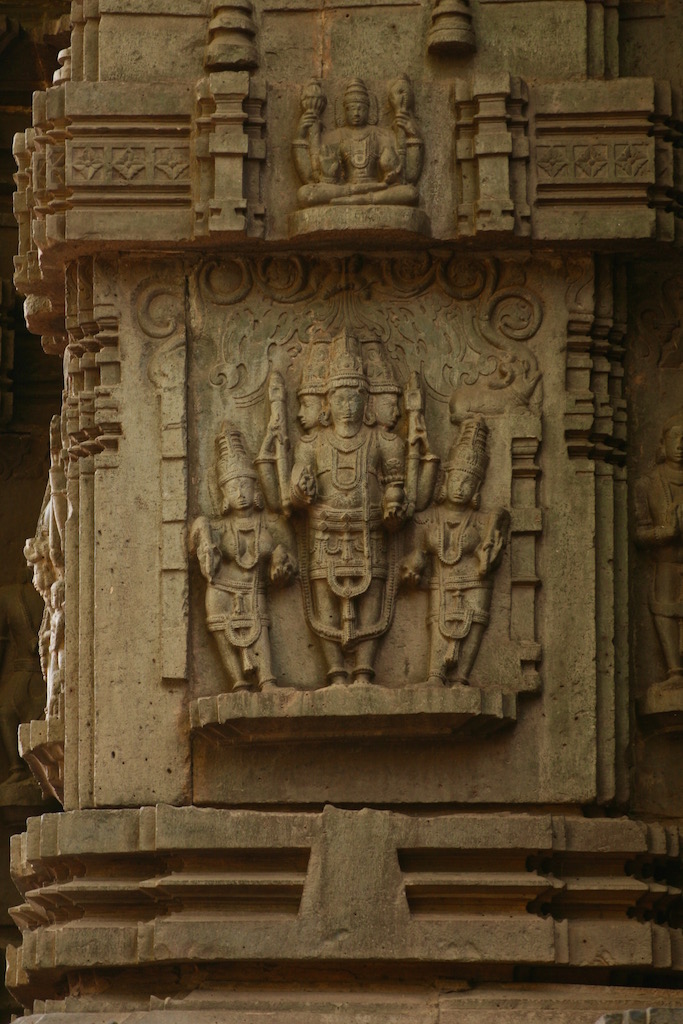

Kopeshwar Temple – Khidrapur

What it cannot make up for in size and scale, the Khidrapur temple makes up in grandeur and ornateness. This temple is dedicated to the wrathful form of Lord Shiva, known as Kopeshwar. Of the Shiva temples, this one is unique, in that the Nandi is absent. We don’t know why.

Legend

Long time ago, there lived a chief of Gods called Daksha. He was married to Prasuti, the daughter of Manu, who bore him sixteen daughters. Satī was the youngest of them all, and had her heart set on Shiva.

Daksha and Shiva did not see eye-to-eye. There was, to say the least, a general animosity; more on Daksha’s side. When Satī was of marriageable age, Daksha held a Swayamvar, where he invited all, except Shiva. Satī had made up her mind about who she would choose, but not seeing Shiva in the assembly, flung the garland in the air and asked of Shiva to accept it. Shiva appeared there, middle of the assembly – garland around his neck. Daksha had no choice, but to grudgingly accept; Satī and Shiva were married.

Much later, Daksha held an ashwamedh (horse sacrifice) – again, all Gods were invited to partake of the offerings of the sacrifice; except Shiva. When Satī heard of this she was furious and after an argument with Shiva proceeded to the sacrifice, uninvited. Some insults ensued, and Satī released an inward consuming fire and died at Daksha’s feet. (some versions say Satī self-immolated in the sacrificial fire)

Shiva soon got to know of this and was consumed with rage. In that state he tore a lock of his hair and flung it to earth, which gave rise to the frightful form of Virbhadrā, who wrecked havoc at the sacrifice. Daksha was beheaded, among other ‘divine’ casualties. Brahmā and Vishṇu had to intervene to stop the carnage. Shiva bestowed a goat’s head to Daksha and made good, all injuries caused. Thus, all was well; all those present bowed to the Trinity, and departed.

History

Construction of this temple was started by the Śilāhāra King, Gandarāditya I, (the youngest of five sons of Mārasimha) around 1126 CE (Some sources put the date at 1028 CE). For more information of dynasties of Maharashtra, see The Dynasties of Maharashtra

The Śilāhāras were originally feudatories of the Rāśtrakuta empire, and ruled in North Konkan, from around 800 CE. By 900 CE, there were three branches of the dynasty; apart from the original North Konkan branch, they now also ruled South Konkan and South Maharashtra (Kolhapur). Gandarāditya I (r. 1108 – 1138), of the Kolhapur branch, started the construction of the Khidrapur temple. Gandarāditya was a prolific temple-builder and is credited for building four temples in the region and providing grants for a few more, including Jain and Buddhist temples. Gandarāditya was succeeded by Vijayāditya and Bhōja II, after which this dynasty came to an end at the hands of the Seuna Yādavs.

Construction of the temple continued for over seventy years during the reign of his successors, Vijayāditya and Bhōja II. The structure was still incomplete when the Yādav king Singhana annexed the Śilāhāra kingdom, and remains such, to this day. Singhana also possibly contributed to the construction of the temple, according to some inscriptions in the temple.

Temple Architecture

The temple consists of the garbha-grha (sanctum), the antarāla (antechamber), the gūḍha-maṇḍapa (enclosed hall) and the raṅga-maṇḍapa, constructed in a row. Usually, there is a dvāra-maṇḍapa in front of such a gūḍha-maṇḍapa but here its place is taken by a detached large octagonal maṇḍapa (called sabhā-maṇḍapa or ranga-maṇḍapa), as in the case of the Sun Temple at Modhera. Inside, are twelve pillars in a circle which open to the sky, because the ceiling was never constructed. It is believed by the local people that a pious man who stands on the slab below that opening, goes to heaven. Hence, it is also called the swarga-maṇḍapa.

The garbha-grha, the antarāla and the gūḍha-maṇḍapa are star-shaped on the outside Their walls are decorated with various images from top to bottom The lowest part of the jaṅghā (pillars) are adorned with beautiful figures of elephants (Gajapeetha), with various Gods such as Indrā, Brahmā and Vishṇu riding them. There are 92 such elephants, 46 on each side. (Adapted from CII Vol. 4)

The construction methodology followed is the dry mortar bedding technique. (ASI, Mumbai Circle)

Here’s another extract (with minor edits for consistency and readability) from the The Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Vol. XXIV – Kolhapur) about Khidrapur:

Khidrapur, lies on the Krishnā river about twelve miles south-east of Shirol. The chief interest of the village is the temple of Kopeshwar which lies in the centre of the village and is 10½’ x 65’ x 52½’ high, to the top of the dome. The walls are made of black stone richly carved and the dome is covered with stucco. To the main building are attached two richly carved sculptured mandaps or vestibules. In the vestibule are two concentric squares; the outer with twenty and the inner with twelve pillars, richly carved. In front of the temple is round roofless structure called the Swarga Mandapa or Heavenly Hall, on the plan of what would be a twenty-rayed star, only that the spaces for four of the rays are occupied by four entrances. On the outside on a low screen wall stand thirty-six short pillars, while inside is a circle of twelve columns. Further from the temple is the nagārkhāna or drum-chamber. The outer walls of the temple are broken at oblique angles as in the Nilang Hemādpanti temple.

By the south door of the temple is a Devgiri Yādav inscription of Sinhadev in Devnāgari dated Shak 1135 (A.D. 1213) granting the village of Khandaleshwar in Miraj for the worship of Kopeshwar.

*

Khidrapur is about 65kms south-east of Kolhapur and well laid out on Google Maps.

Gallery

References

- Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Vol. 6 Inscriptions of the Śilāhāras

- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency Vol. 24 – Kolhapur

- ASI Mumbai Circle. (n.d.). Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.asimumbaicircle.com/m_kolhapur.html

- Gupta, S. P., & Asthana, S. P. (2009). Elements of Indian Art: Including Temple Architecture, Iconography & Iconometry. New Delhi: Indraprastha Museum of Art and Archaeology.

- Nivedita, S., & Coomaraswamy, A. K. (n.d.). Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists.

- Shilahara Dynasty. (2017, March 26). Retrieved March 30, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shilahara

- Virabhadra. (2017, March 28). Retrieved March 30, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virabhadra

Gyaraspur Galleries | Chaukhamba & Hindola Torana

The Kachchhapaghata dynasty ruled the north-western parts of Madhya Pradesh during the 10th and 12th CE. They are assumed to be the progeny of the Nāgas and were the vassals of the Gurjara-Pratiharas and later, of the Chandelas of Central India.

Hindola Toran & Chaukhamba, Gyaraspur

Click to see details

This dynasty contributed much to art and architecture and many temples were built under their patronage. Their early work follows the Gurjara-Pratihara style, and later developed unique and new trends in temple construction.

The Vishnu Temple (some sources refer to it as a Trimurti temple) at Gyaraspur is one example of the Kachchhapaghata style of architecture. Not much remains of this temple except the four pillars (Chaukhamba) of the central sanctum and a gateway (Hindola Torana).

Monument Details

Click to see details

There are ornate carvings on the two sandstone pillars of the Hindola Torana depicting the ten incarnations of Vishnu; these beams carry two horizontal beams, with two ornamental arches between the two beams. This gateway is the southern entrance to the east-facing temple, which is believed to have been 150 ft east to west and about 85 ft north to south. The four pillars, Chaukhamba, are the central pillars of the hall, which are equally adorned by ornate carvings on all sides.

Gallery | Dashavataar, Hindola Toran

Click to see details

References

- Gyaraspur – A Heritage of Excellence. (n.d.). Retrieved March 02, 2017, from http://puratattva.in/2010/04/27/gyaraspur-a-heritage-of-excellence-54

Jain, K. C. (1972). Malwa through the ages, from the earliest times to 1305 A.D. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 432-433 - Journal of History & Social Sciences. (n.d.). Retrieved March 02, 2017, from http://jhss.org/archivearticleview.php?artid=145

- Kachchhapaghata dynasty. (2017, February 23). Retrieved March 02, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kachchhapaghata_dynasty

- Vishnu Temple (Chaukhambha and Hindola-Torana). (n.d.). Retrieved March 2, 2017, from http://www.tspasibhopal.nic.in/project/expl_Khadwaha_Ashok_nagar_mp_2009_10/temple/project11_12_vishnu_temple_vidisha.html

Gallery | Hessing’s Tomb, Agra

Text of the information plaque at Hessing’s Tomb, Agra and the Tomb inscription (below gallery)

Hessing’s Tomb (1803 AD)

This is the tomb of Col. John William Hessing who was Dutch and came to Ceylon as a freelance adventurer. He participated in the battle of Kandy in 1765. Then, he served the Nizam of Hyderabad and in 1784, entered the service of the Maratha chief Mahadji Sindhia. He fought several battles under the command of the French general De Boigne. Mahadji trusted him the most, and Hessing accompanied him to Poona in 1792. On Mahadji’s death there in 1794 he returned to Agra which was held by Marathas. He was made commandant of the fort and its Maratha garrison in 1799. He died here on 21 July 1803. The fort was captured by the British the same year. His tomb was built by his children.

It stands on a square platform which 11.25 feet high and 58 feet side, containing a crypt with the real grave and a corridor around it. An octogonal chabutra is attached to each corner in the form of a mini-tower. Twin stairways are also attached to it on the western side of the platform measuring 22 x 8.75 feet. The tomb reposes effectively in the middle of the main platform. It is square in plan with 34.75 feet side and 28.5 feet in height. Each facade has an iwan in the middle, flanked on either side by ornamental peshtaq (alcoves). It is essentially a Mughal design. Slender turrets are attached to the central iwan frame. They are crowned by pinnacles. Square turrets, 2 feet side, are attached to the corners of the tomb. These have vertical flutes and are surmounted by beautiful square chhatris. The tomb is roofed by a double-dome, crowned by mahapadma (Sheath of lotus petals) and Kalash finial. With pinnacles and chhatris of the turrets, it makes up a perfect superstructure. The interior is a square chamber 17.75 feet side with ribs-and-panels soffit. The cenotaph bears an inscription in English. As a whole it is a perfectly balanced and beautiful building and is rightly called “A Taj in miniature.” This is in fact, the most beautiful tomb of a European at Agra, and probably in India. Though a Dutch tomb, it belongs in letter and spirit, to Agra and the art of the Jamuna-Chambal region. It marks continuance of Mughal “ideas”, “feelings”, and “skills” in 19th Century A.D

Tomb Inscription

1803 — HESSING, J. W. Colonel

John William Hessing, late a Colonel in the service of Maharaja Daulat Rao Sindhia, who, after sustaining a lingering and very painful illness for many years with true Christian fortitude and resignation, departed this life, 21st July 1803, aged 63 years, 11th months, and 5 days. As tribute of their affection and regard this monument is erected to his beloved memory by his disconsolate widow, Anne Hessing, and afflicted sons and daughters, George William Hessing, Thomas William Hessing and Magdalene Sutherland. He was a native of Utrecht in Holland and came out to Ceylon in the Military service of the Dutch E. I. Company in the year 1752, and was present at the taking of Candia by their troops. Five years afterwards he returned to Holland and came out again to India in the year 1733, and served under the Nizam of the Deccan. In the year 1784, he entered into the service of Madho Rao Sindhia and was engaged in the several battles that led to the aggrandizement of that Chief and wherein he signalized himself so by his bravery as to gain the esteem and approbation of his employer, more particularly at the battle of Bhondagaon near Agra in the year 1787, which took place between this Chief and Nawab Ismael Beg, when he then became a Captain, and was severely wounded. On the death of Madho Rao Sindhia in 1793, he continued under his successor, Daulat Rao Sindhia, and in 1798 he attained to the rank of Colonel and immediately after to the command of the Fort and City of Agra, which he held to his death.

[There is little to be added to the history given in the epitaph. He was born in 1740. There is no record of his adventures between 1763 and 1784. He served in De Boigne’s brigades of regular troops. The “several battles” are Lalsot, Chaksana and Patan. After Patan, he quarrelled with De Boigne and left him but Madhoji Scindia employed him to raise a bodyguard for him. which grew to 4 battalions. In 1800 he was compelled to resign his command by ill- health and retired as commandant of Agra to that city. He is described as a “good, benevolent man and a brave soldier.” His tomb is a miniature of the Taj in red Agra sandstone.]

References

- Blunt, Edward. List of inscriptions on Christian tombs and tablets of historical interest in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. Allahabad: Printed by W.C. Abel, Offg. Supdt., Govt. Press, United Provinces, 1911. Print. p. 46-47 Download.

Gallery | Laxmi Narayan Temple, Orchha

This temple, a blend of temple and fort architecture, was built in 1622 CE by Vir Singh Deo of Bundelkhand, and was refurbished by Prithvi Singh during 1793 CE.

The temple has a rectangular layout, with entrances at one of the four projecting bastions. It appears triangular in shape, from these points. The walls of the inside corridors of the temple are profusely adorned with beautiful murals and frescos. These include an attack on Jhansi, of Krishna, Ganesha, depiction of a Parthian shot, and several other local stories.

Click, to see large images.

Bidar Fort

Sultan Alla-Ud Din Bahman of the Bahmanid Dynasty shifted his capital from Gulbarga to Bidar in 1427 and built his fort along with a number of monuments in it. The fort was captured by Bijapur Sultanate in 1619–20, but fell to the Mughals in 1657; as a part of a Peace treaty.

The fort has five gates, 37 bastions and is surrounded by multiple moats. It houses multiple monuments, of which Rangin Mahal is the most decorated of them all. [Link]

Gallery | Sultan Bateri, Boloor, Mangaluru

Mangalore was an important town even during the early historic times referred to by Greek Geographers Pliny (23 AD) and Ptolemy (c. 150 AD). It was the capital of the Alupa rulers for a long time. In 1526 AD Mangalore was taken over by the Portuguese who were subsequently expelled by the Nayakas of Bidnur in the early 18th century. Haider Ali captured this place in 1763. In 1768, it went into the hands of the British.

Sultan Bateri, a watch tower, is said to have been built by Tipu Sultan to contain the warships into the Gurpur River. Though it is a simple watch tower, it looks like a miniature fortress with its many musket holes for mounting canons all round.

~ ASI Plaque at Sultan Bateri (Battery)

Click the images to view large images.